2. Working with files and directories

Working with Files and Directories

Unix

Things covered here:

- Working with files

- What a plain-text file is

- Introduction to a command-line text editor:

nano- Working with directories

Working with plain-text files and directories

Next we’re going to look at some more ways to learn about and manipulate file and directories at the command line.

To be sure we are still working in the same place, let’s run:

cd ~/unix_intro

Working with files

We will often want to get a look at a file to see how it’s structured or what’s in it. We’ve already used one very common tool for peeking at files, the head command. There is also tail, which prints the last 10 lines of a file by default:

head example.txt

tail example.txt

Programs like these can be especially helpful if a file is particularly large, as head will just print the first ten lines and stop. This means it will be just as instantaneous whether the file is 10kB or 10GB.

Another standard useful program for viewing the contents of a file is less. This opens a searchable, read-only program that allows us to scroll through the document:

less example.txt

To exit the less program, press the “q” key.

The wc (word count) command is useful for counting how many lines, words, and characters there are in a file:

wc example.txt

wc -l example.txtAdding the optional flag

The most common command-line tools like these and many others we’ll see are mostly only useful for operating on what are known as plain-text files – also referred to as “flat files”.

BONUS ROUND: What’s a plain-text file?

A general definition of a plain-text file is a text file that doesn’t contain any special formatting characters or information, and that can be properly viewed and edited with any standard text editor.

Common types of plain-text files are those ending with extensions like “.txt”, “.tsv” (tab-separated values), or “.csv” (comma separated values). Some examples of common file types that are not plain-text files would be “.docx”, “.pdf”, or “.xlsx”. This is because those file formats contain special types of compression and formatting information that are only interpretable by programs specifically designed to work with them.

A note on file extensions

File extensions themselves do not actually do anything to the file format. They are mostly there just for our convenience/organization – “mostly” because some programs require a specific extension to be present for them to even try interacting with a file. But this has nothing to do with the file contents, just that the program won’t let us interact with it unless it has a specific extension.

Copying, moving, and renaming files

WARNING!

The commands cp and mv (copy and move) have the same basic structure. They both require two positional arguments – the first is the file we want to act on, and the second is where we want it to go (which can include the name we want to give it).

To see how this works, let’s make a copy of “example.txt”:

ls

cp example.txt example_copy.txt

ls

By just giving the second argument a name and nothing else (meaning no path in front of the name), we are implicitly saying we want it copied to where we currently are.

To make a copy and put it somewhere else, like in our subdirectory “data”, we could change the second positional argument using a relative path (“relative” because it starts from where we currently are):

ls data/

cp example.txt data/example_copy.txt

ls data/

To copy it to that subdirectory but keep the same name, we could type the whole name out, but we can also just provide the directory and leave off the file name, and it will automatically keep the same original name:

cp example.txt data/

ls data/

If we wanted to copy something from somewhere else to our current working directory and keep the same name, we can use another special character, a period (.), which specifies the current working directory:

ls

cp experiment/notes.txt .

ls

The mv command is used to move files. Let’s move the “example_copy.txt” file into the “experiment” subdirectory:

ls

ls experiment/

mv example_copy.txt experiment/

ls

ls experiment/

The mv command is also used to rename files. This may seem strange at first, but remember that the path (address) of a file actually includes its name too (otherwise everything in the same directory would have the same path).

ls

mv notes.txt notes_old.txt

ls

To delete files there is the rm command (remove). This requires at least one argument specifying the file we want to delete. But again, caution is warranted. There will be no confirmation or retrieval from a waste bin afterwards.

ls

rm notes_old.txt

ls

A terminal text editor

It is often very useful to be able to generate new plain-text files quickly at the command line, or make some changes to an existing one. One way to do this is using a text editor that operates at the command line. Here we’re going to look at one program that does this called nano.

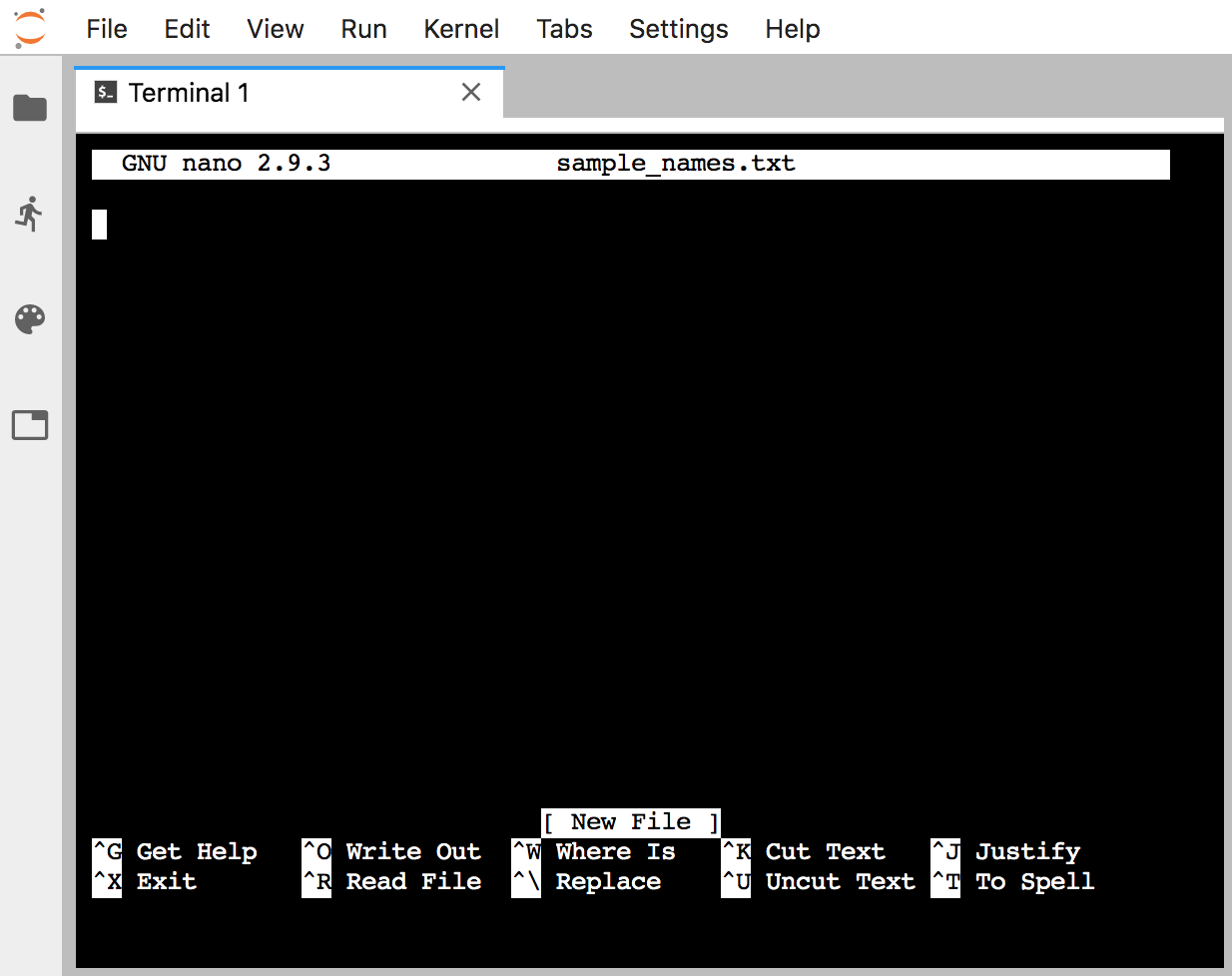

When we run the command nano it will open a text editor in our terminal window. If we give it a file name as a positional argument, it will open that file if it exists, or it will create it if it doesn’t. Here we’ll make a new file:

nano sample_names.txt

When we press return, our environment changes to this:

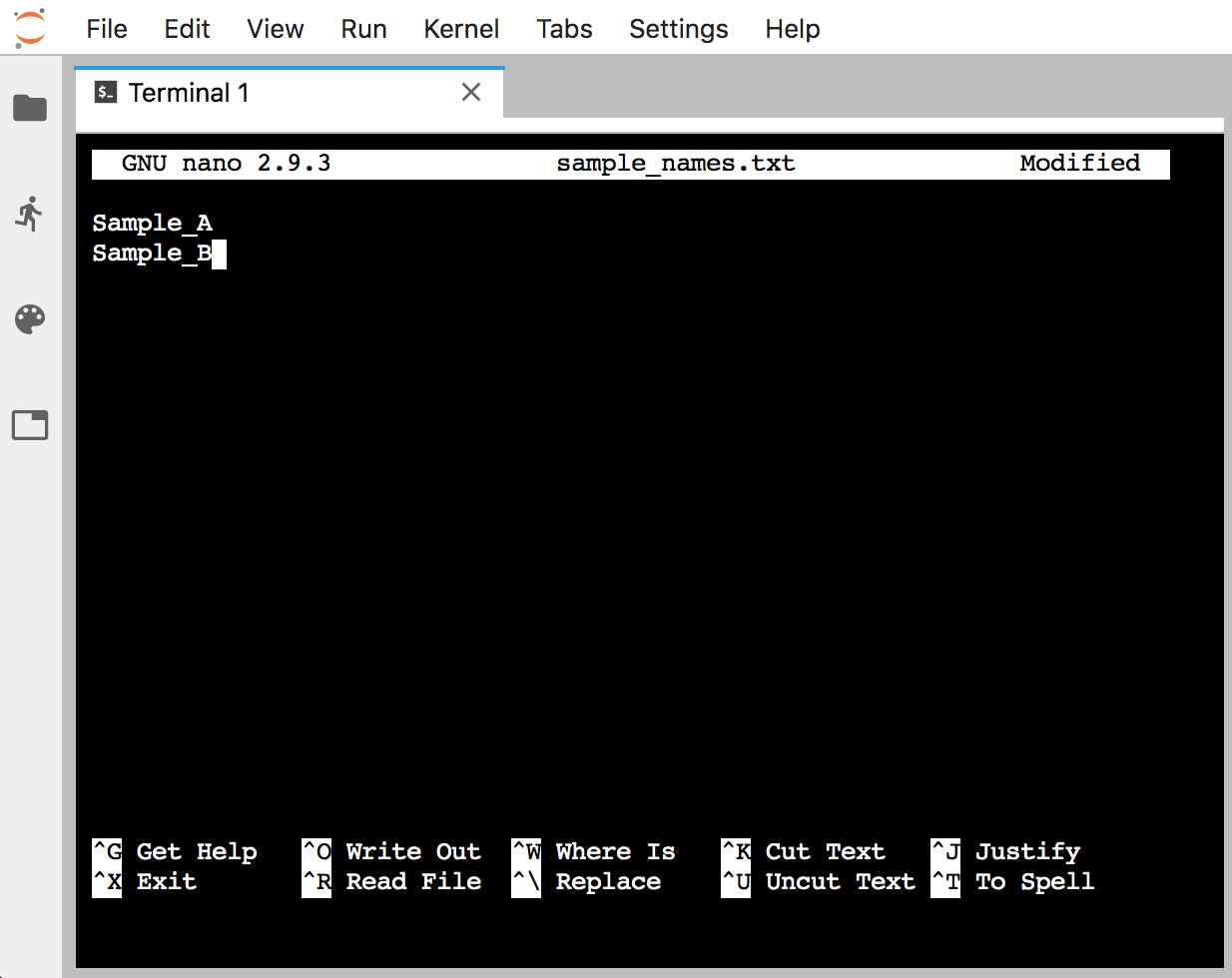

Now we can type as usual. Type in a couple of sample names, one on each line – it doesn’t matter what the names are:

Afterwards, to save the file and exit, we need to use some of the keyboard shortcuts listed on the bottom. “WriteOut” will save our file, and the ^O represents pressing ctrl + o together (it doesn’t need to be a capital “O”). This will ask us to either enter or confirm the file name, we can just press return. Now that it is saved, to exit we need to press ctrl + x.

And now our new file is in our current working directory:

ls

head sample_names.txt

NOTE: Quickly googling how to get out of things like

nanothe first 15 times we use them is 100% normal!

Working with directories

Commands for working with directories for the most part operate similarly. We can make a new directory with the command mkdir (for make directory):

ls

mkdir subset

ls

And similarly, directories can be deleted with rmdir (for remove directory):

rmdir subset/

ls

The command line is a little more forgiving when trying to delete a directory. If the directory is not empty, rmdir will give us an error.

rmdir experiment/

Summary

So far we’ve only seen individual commands and printing information to the screen. This is useful for in-the-moment things, but not so much for getting things done. Next we’re going to start looking at some of the things that make the command line so versatile and powerful, starting with redirectors and wildcards!

Commands introduced:

| Command | Function |

|---|---|

head |

prints the first lines of a file |

tail |

prints the last lines of a file |

less |

allows us to browse a file (exit with q key) |

wc |

count lines, words, and characters in a file |

cp |

copy a file or directory (use with caution) |

mv |

mv a file or directory (use with caution) |

rm |

delete a file or directory (use with caution) |

mkdir |

create a directory |

rmdir |

delete an empty directory |

nano |

create and edit plain text files at the command line |

Special characters introduced:

| Characters | Meaning |

|---|---|

. |

specifies the current working directory |