Why is this all worth it?

Everyday Examples

Unix

It can be tough to see why these things are useful before you are actually using them regularly, and it’s not that easy for someone else to demonstrate the general utility of standard unix commands, but I’m going to throw some real-life examples up here of things that were made easier because of them. It is assumed we’re already a little comfortable with the command line and some of the most commonly used commands, but if not, be sure to check out the Unix crash course 🙂

Getting started

If you’d like to follow along here, you can get the mock data we’ll be working with by coping and pasting these commands into your terminal.

cd ~

curl -O https://AstrobioMike.github.io/tutorial_files/bash_why_temp.tar.gz

tar -xvf bash_why_temp.tar.gz

rm bash_why_temp.tar.gz

cd bash_why_temp

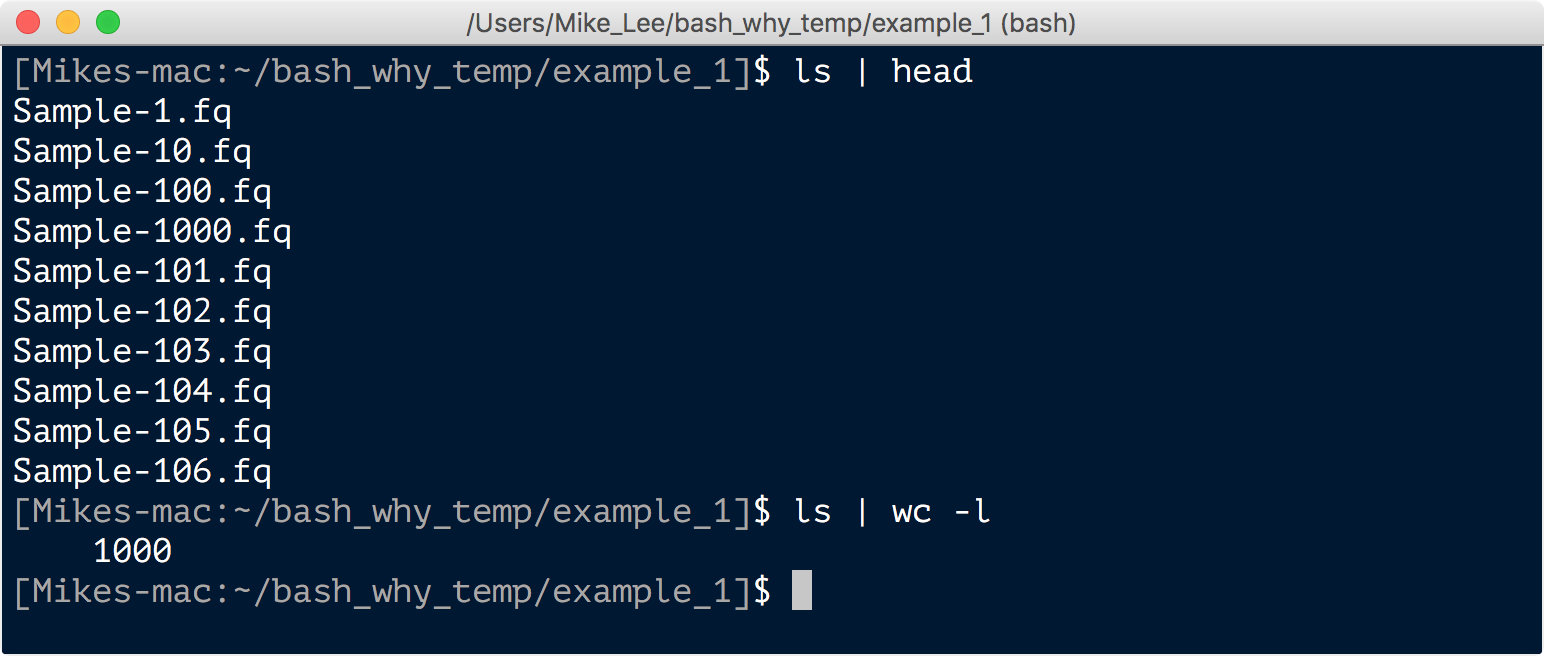

Example 1 - Renaming 1,000 files

So the setup is we have 1,000 files that have names like “Sample-1.fq”, “Sample-2.fq”, etc., but to use the program we want to use we need the filenames to contain an underscore instead of a dash, like “Sample_1.fq”, “Sample_2.fq”, etc. Time for bash to the rescue!

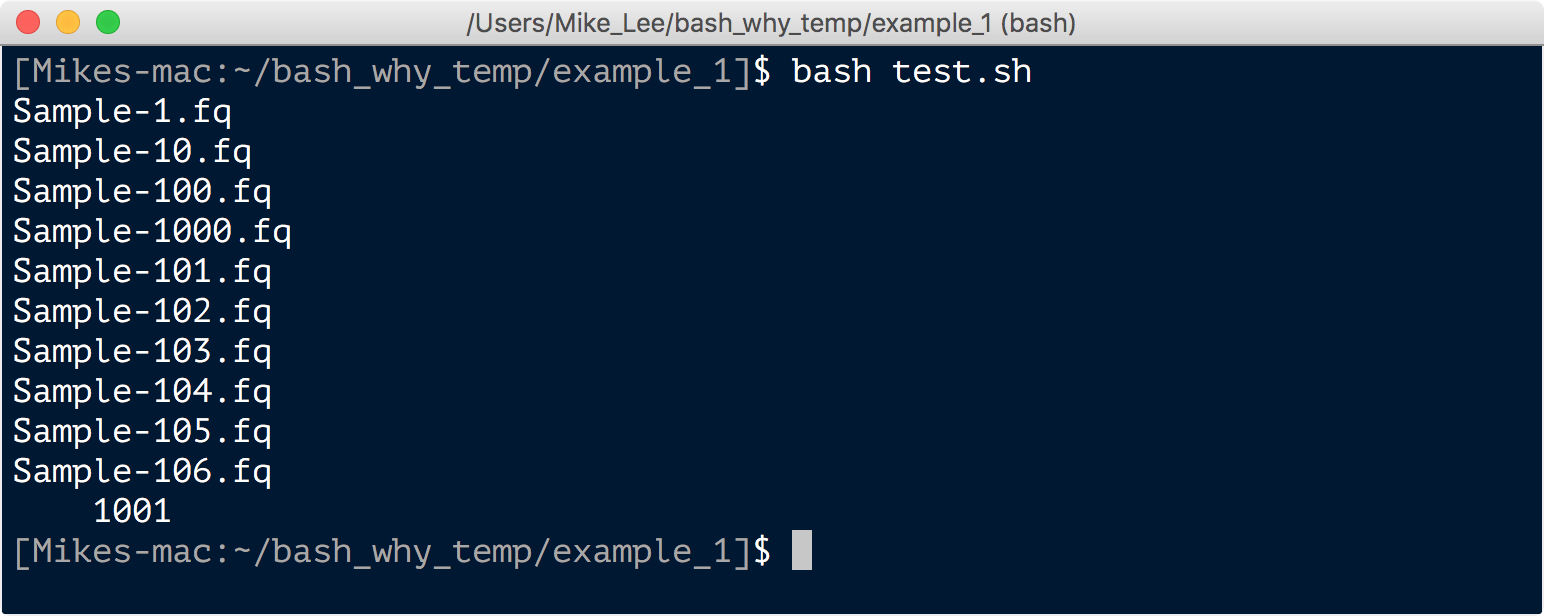

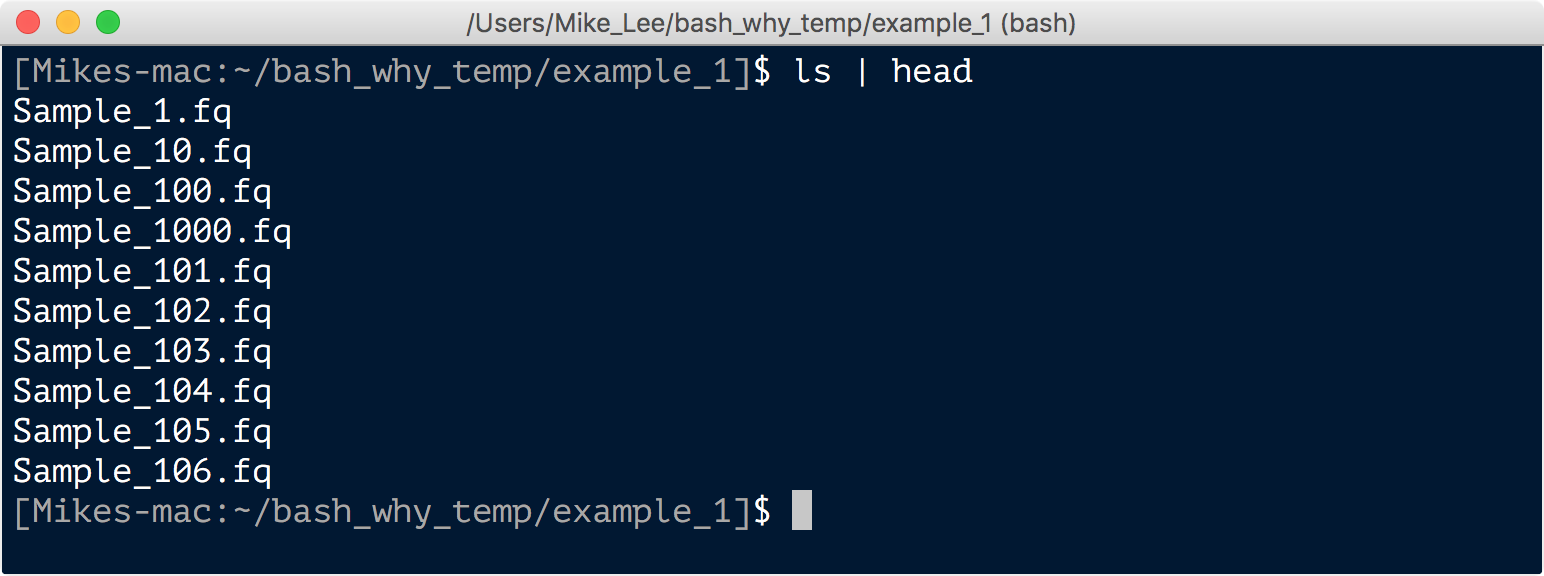

Our example_1 directory holds our 1,000 problematic files.

ls | head

ls | wc -l

Here’s the approach. We covered in the intro to bash page how to rename files with the mv command, so we already know we could easily change one file like this: mv Sample-1.fq Sample_1.fq. But of course that doesn’t scale, and is just as bad us doing this one at a time in the Finder window. Instead, we are going to make and do this with a bash script. A bash script isn’t anything special, it’s just a bunch of individual bash commands one line after another. To demonstrate that, let’s make a script out of the two commands we just ran when looking at our files.

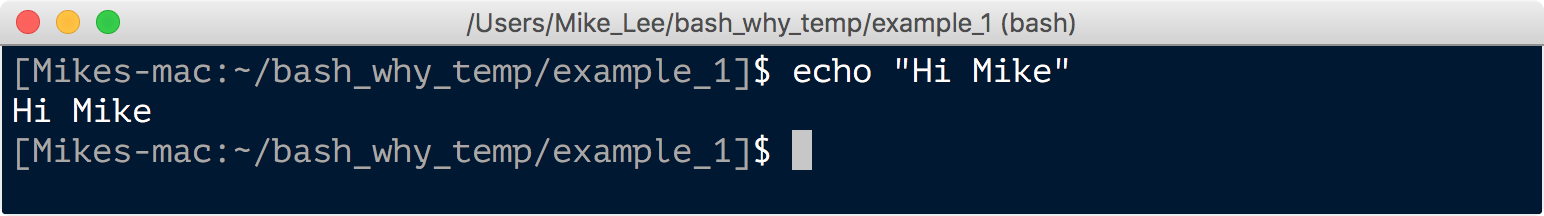

echo is a command that will spit back out whatever you tell it:

echo "Hi Mike"

Seems a little useless at first (unless you’re lonely, of course 😢 ). But its utility makes more sense when you use redirectors to send things somewhere else. For example, instead of using nano like we’ve done before to make a new file, we can make our bash script with the echo command:

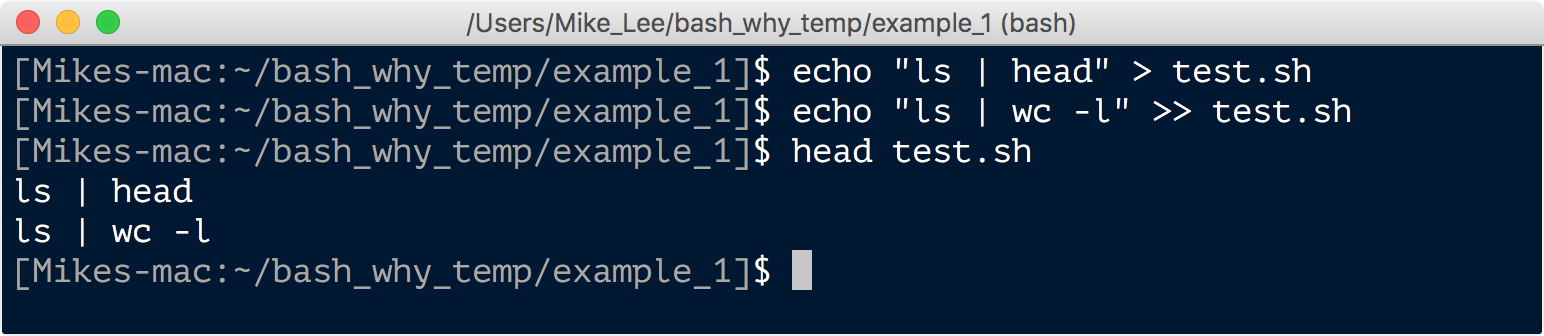

echo "ls | head" > test.sh

echo "ls | wc -l" >> test.sh

head test.sh

The first command redirected “ls | head” into and created the file named “test.sh” (the .sh extension is for “shell” and is the typical extension used for bash scripts). And the second command appended “ls | wc -l” to that file. Then, as we see with head, those are the two lines in the file. We can now run this as a bash script. That’s done by putting bash in front of the file name that is the script (so now bash is the command, and test.sh is a positional argument telling it what to operate on):

bash test.sh

And that ran those commands just the same as if we entered them one at a time interactively. Also notice our ls | wc -l command gave us 1,001 files this time, because there is now also that “test.sh” file in there. If we run ls *.fq | wc -l, we’ll get our 1,000 again.

So back to the task at hand, we are going to make a bash script that has our 1,000 mv commands in it, that will then run as if we entered them all one at a time. This assumes already having gone through the unix introduction in order to be familiar with the few commands here, so if it is confusing, run through that when you can (particularly the six glorious commands page), but here’s the whole process:

# getting all original file names in a file

ls *.fq > orig_filenames

# changing what we want to change, and saving these new names in a second file

tr "-" "_" < orig_filenames > new_filenames

# sticking them together horizontally with a space between them

paste -d ' ' orig_filenames new_filenames > both_filenames

# adding 'mv ' in front of them, just like we would when entering the command by itself

sed 's/^/mv /' both_filenames > rename_all.sh

# getting read of intermediate files

rm *filenames

# and running our little script to rename them all for us :)

bash rename_all.sh

And that’s it. If we peek at our files now we see they all have underscores instead of dashes:

Example 2 - Making a barcode fasta file to demultiplex samples

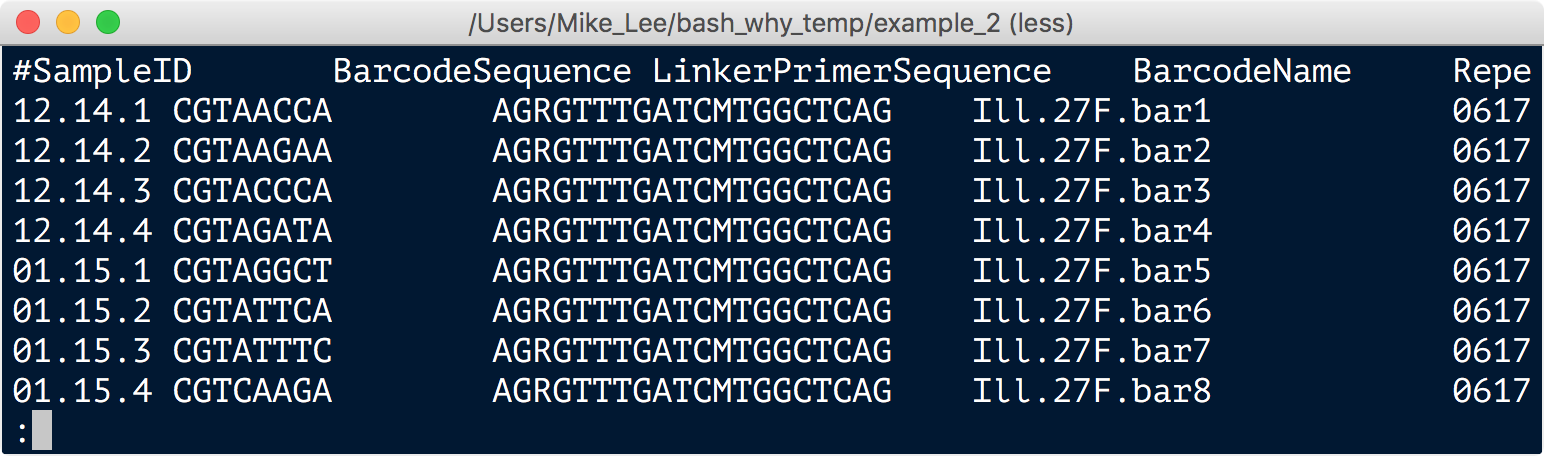

In this case we have a mapping file from the sequencing facility that looks like this:

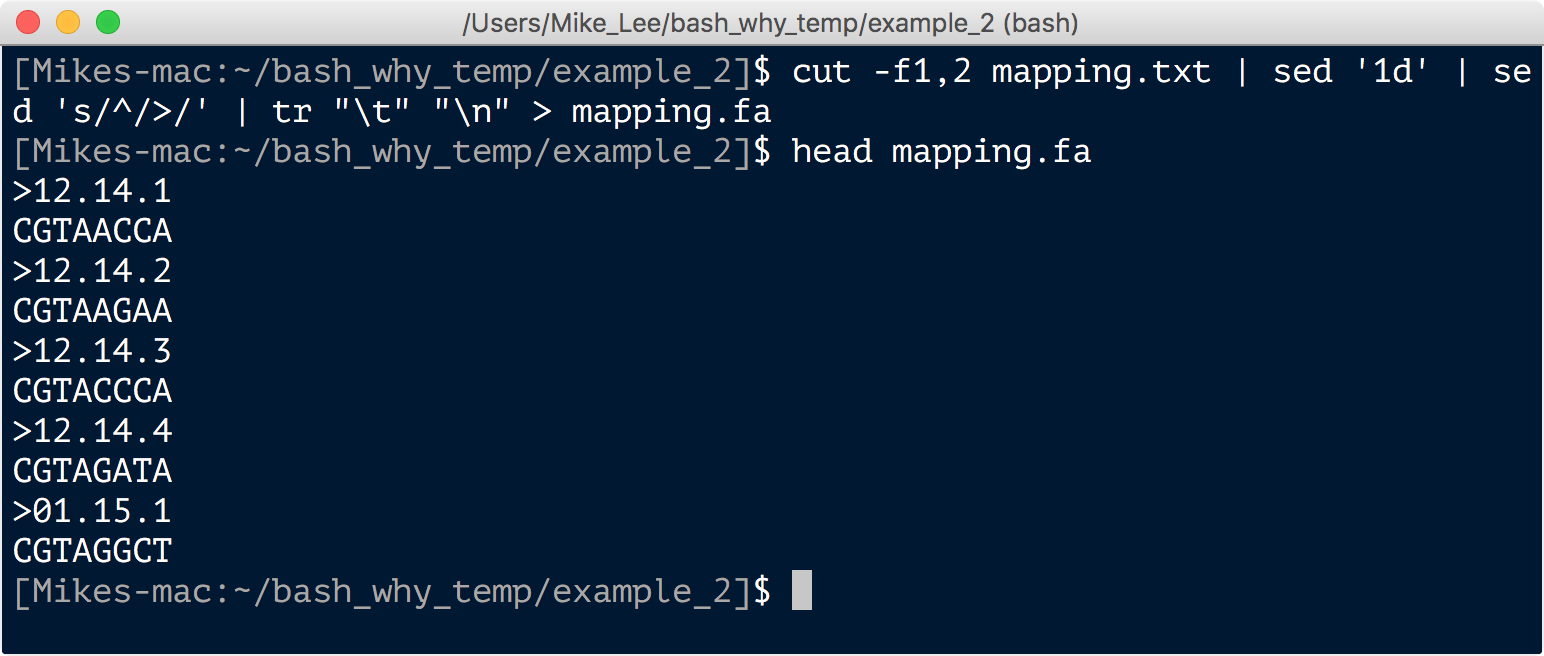

Some sequencing facilities send you back your samples all mixed together, and you need to separate the sequences based on the barcode they have that ties them to which sample they came from. The barcode in this file is the second column, and the sample is specified in the first column. Some programs that do this demultiplexing step require a fasta file to be the “mapping file” to tell it which barcodes belong to which samples. We’re going to make that fasta file from this starting file with just a few commands strung together:

cut -f 1,2 mapping.txt | sed '1d' | sed 's/^/>/' | tr "\t" "\n" > mapping.fa

Example 3 - Counting specific amino acids in lots of tables

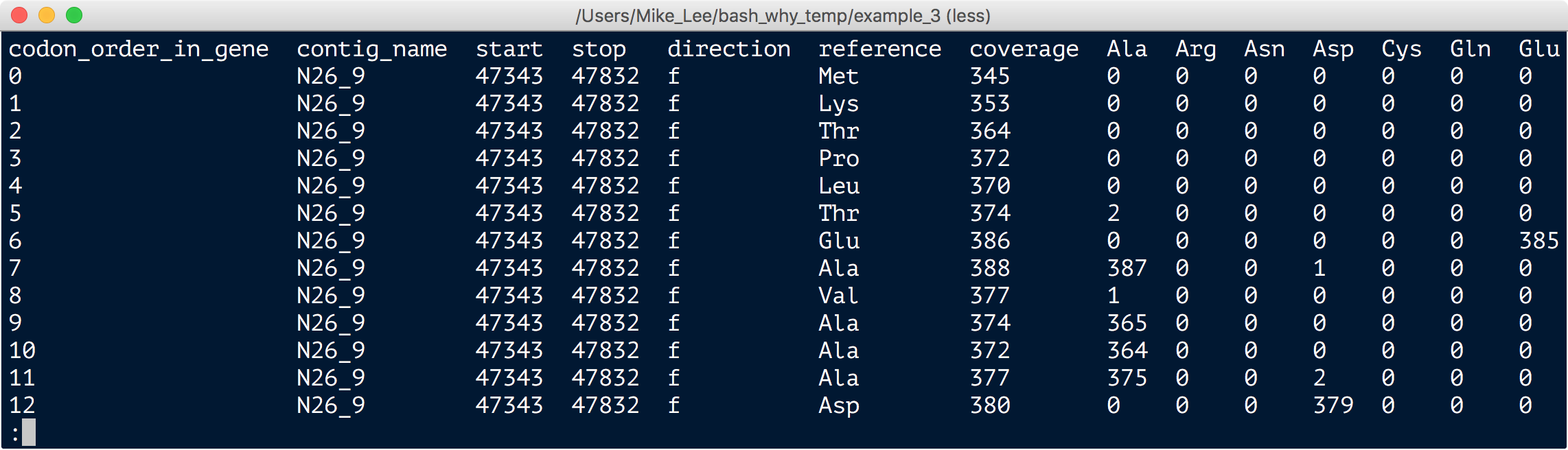

Recently my good ‘ol buddy Josh Kling was telling me about this paper by Pittera et al., which is about the thermostability of some Synechococcus proteins. They hypothesized that a particular amino acid (position number 43) would more often be alanine in warmer temperature waters, and glycine in colder temperature waters. Having been working on genomics and pangenomics of Syn, I had mapped metagenomic data from about 100 samples from the TARA Oceans global sampling project. So we realized we already had some data we could look at to test this hypothesis just sitting in the computer. All the information was already in the mapping files, we just needed to pull it out. The first part of that was made that easy was thanks to anvi’o helping to parse the mapping files and give us nice tables like this that we have in our example_3 working directory:

column -ts $'\t' ANW_141_05M_24055_AA_freqs.txt | less -S

To get this we told anvi’o which gene we were interested in and it spit out this nice table for that specific gene for every environmental sample we had. This is telling us what the Syn population at a specific sample site uses for amino acids at each position within this gene. In the table, every row is an amino-acid position in this one gene, and the columns towards the right tell us the total coverage for that position, and the frequency of each amino acid at that position.

So we had lots of these tables, because there were 32 reference genomes and each had a copy of the gene. Then there were about 32 samples that had greater than 100X coverage that we looked at. In our example here we’re only working with one of these samples, so we have just 32 tables for the 32 copies of genes, but the principle is the same.

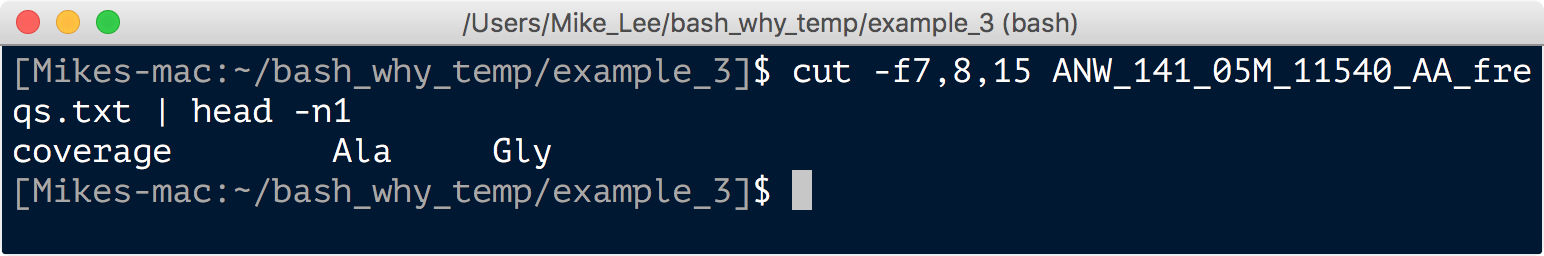

Back to the task at hand, we want to know how often Syn uses an alanine at amino acid position 43 vs how often it uses glycine at that position. To answer that we needed to pull the appropriate row from all of these tables, and then sum the “coverage”, “Ala”, and “Gly” columns for comparison. These are columns 7, 8, and 15, which we can double check like so:

Now that we know we have the right columns, here’s the fun part:

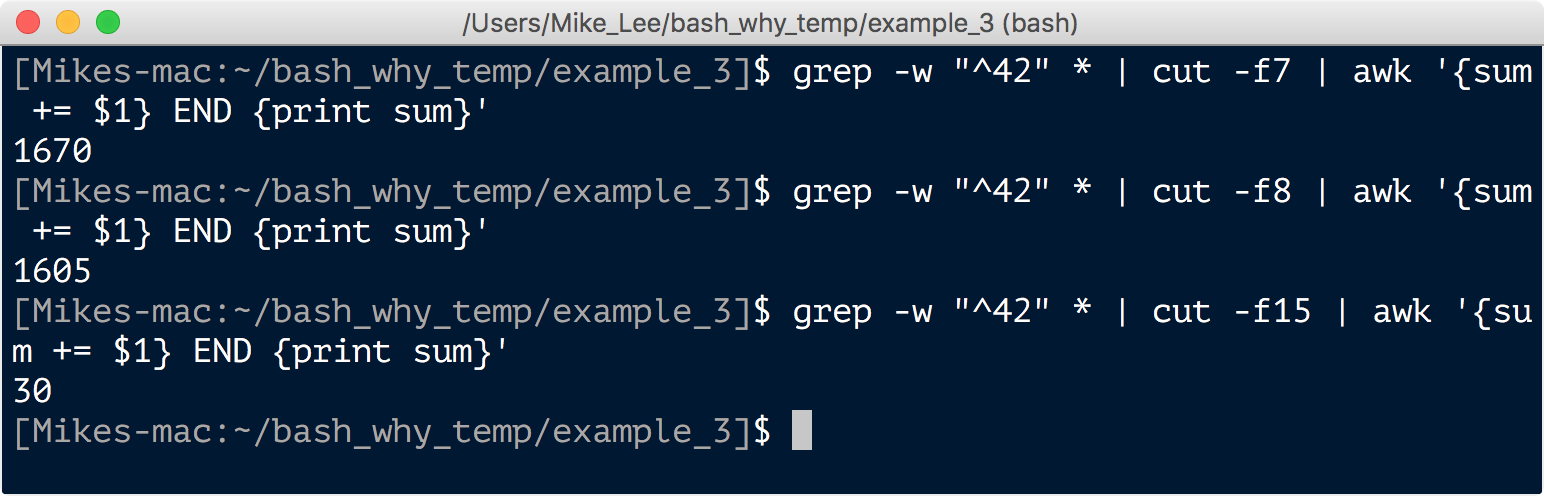

grep -w "^42" * | cut -f7 | awk '{sum += $1} END {print sum}'

grep -w "^42" * | cut -f8 | awk '{sum += $1} END {print sum}'

grep -w "^42" * | cut -f15 | awk '{sum += $1} END {print sum}'

And we see at this particular site the coverage of this specific amino acid position was 1,670, it was an alanine 1,605 of those times, and a glycine only 30 of those times. And sure enough this was a warmer site and we saw the exact opposite when looking at colder sites. Pretty cool! Props to Piterra et al..

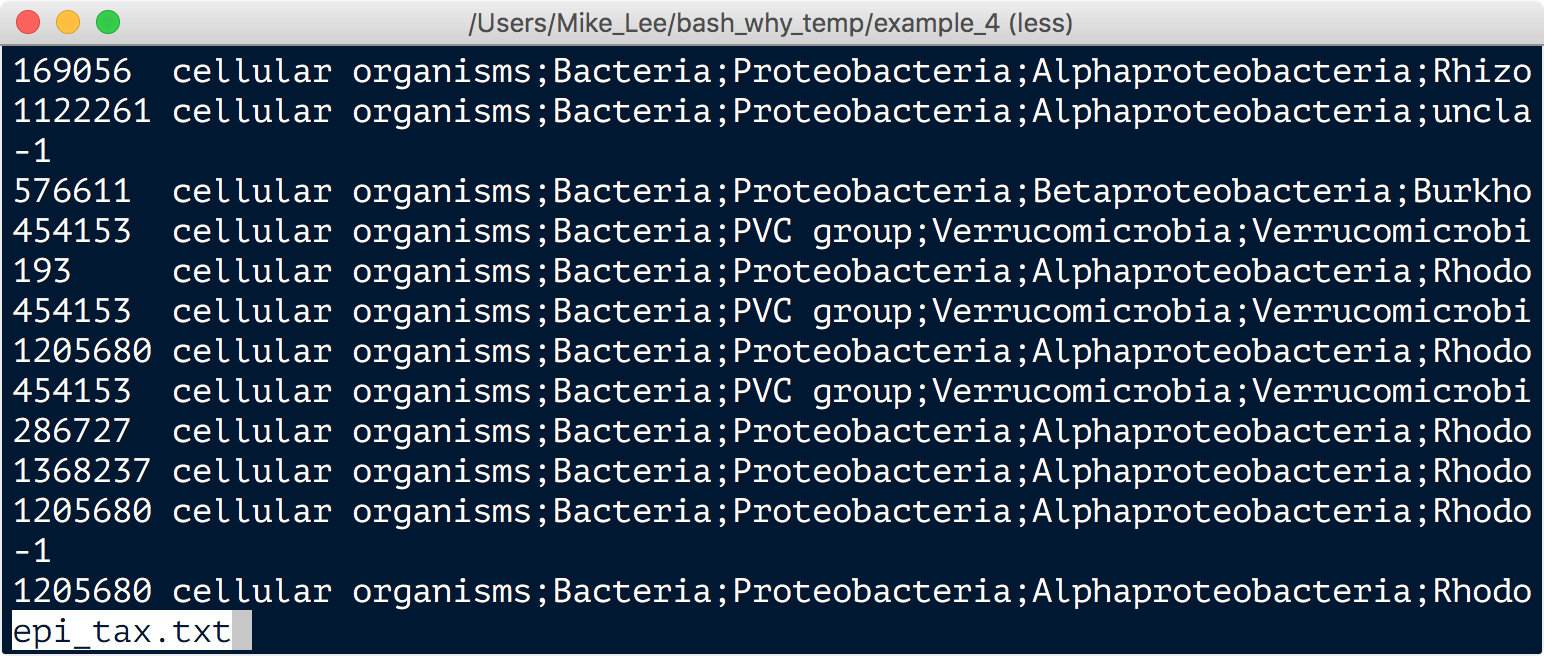

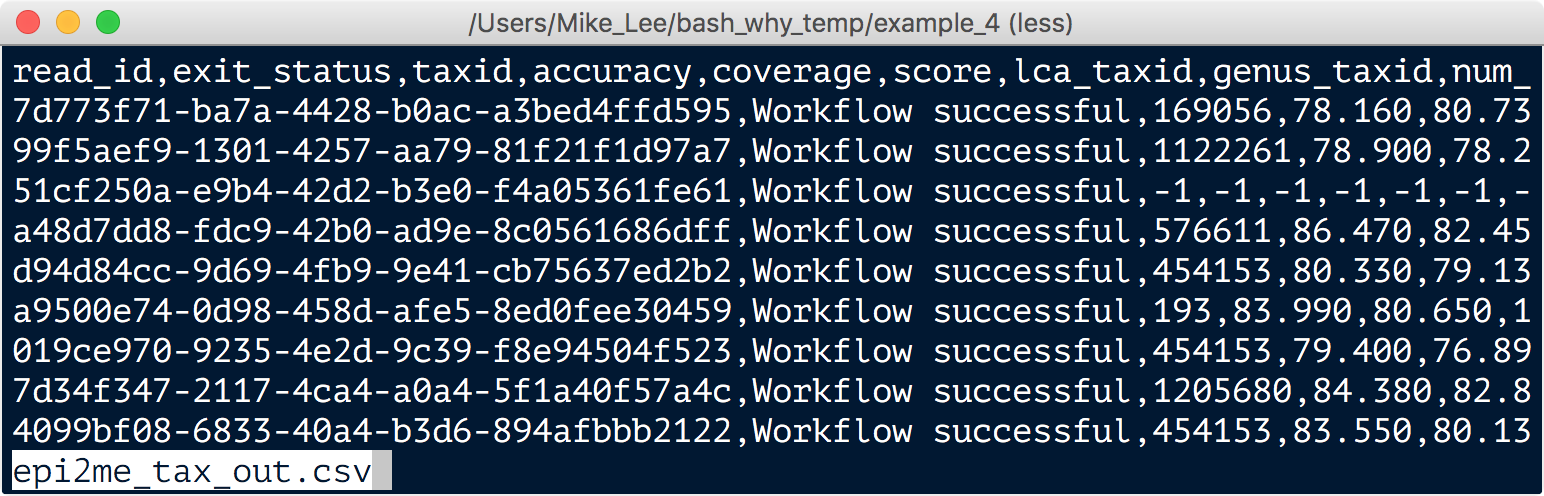

Example 4 - Converting NCBI taxon IDs to organism lineages

Recently some collaborators did some sequening with Nanopore’s MinION sequencer. This is a “real-time” sequencer that is trying to be as user-friendly as possible so just about anyone can sequence DNA anywhere. They have a whole workflow setup so you can just stream the data to a server as you sequence and it will run things through a taxonomy classifier, BUT for some strange reason it only gives you tables with NCBI taxonomy IDs and no actual organism information. My collaborators were kind of stuck there for a bit and asked me for help.

Fortunately there is a nice tool called taxonkit (which is in our working directory) that will convert these IDs to organism lineages like we want, but we first have to parse the output from the MinION workflow, which looks like this:

Mixed in that mess, column 3 has the “taxids” we’re looking for. So first we need to cut them out and put them into their own file.

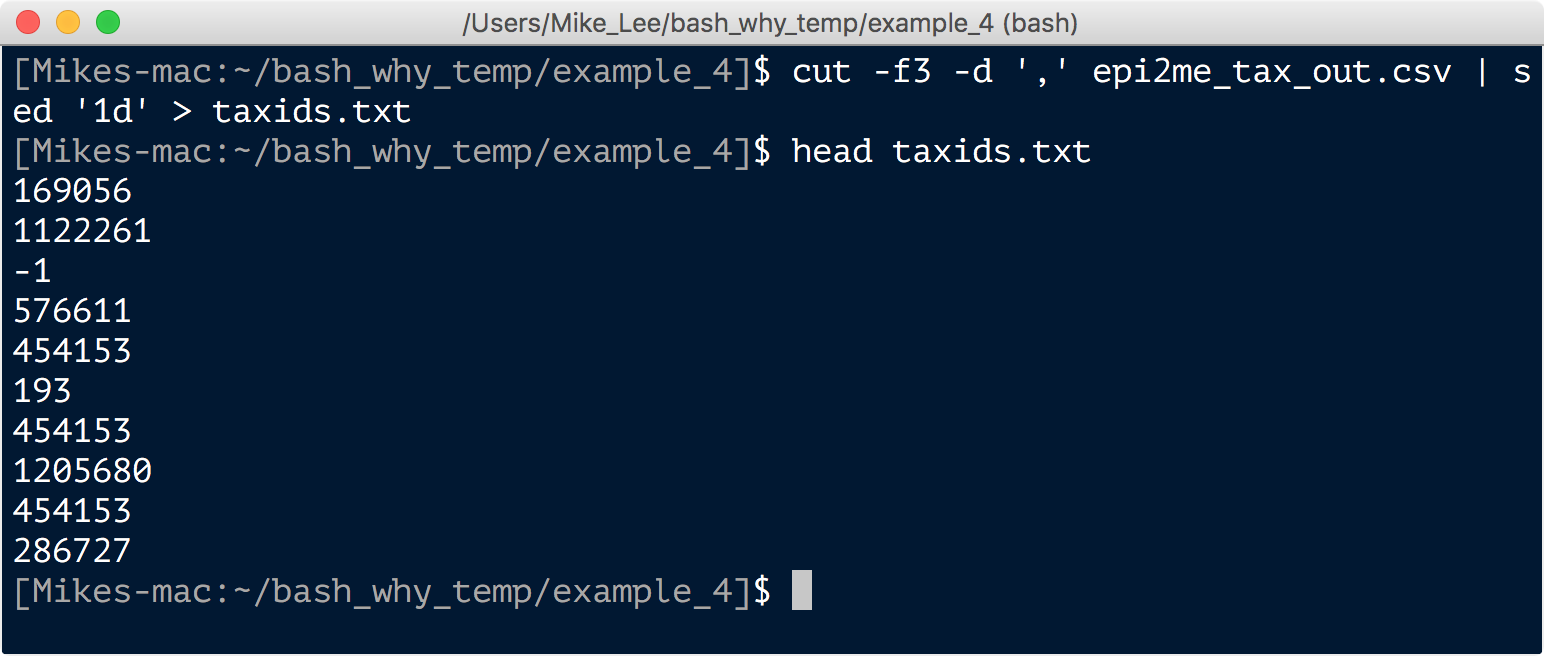

cut -f 3 -d ',' epi2me_tax_out.csv | sed '1d' > taxids.txt

head taxids.txt

And now we can just provide that file to the taxonkit program like such:

./taxonkit lineage taxids.txt -o epi_tax.txt --names-file names.dmp --nodes-file nodes.dmp

And a few seconds later, we have our nice, actually useful, taxonomy table: