Amplicon and metagenomics overview

Amplicon and Metagenomics Overview

This page presents a broad-level overview of amplicon sequencing and metagenomics as applied to microbial ecology. Both of these methods are most often applied for exploration and hypothesis generation and should be thought of as steps in the process of science rather than end-points – like all tools of science 🙂

Amplicon sequencing

Amplicon sequencing of marker-genes (e.g. 16S, 18S, ITS) involves using specific primers that target a specific gene or gene fragment. It is one of the first tools in the microbial ecologist’s toolkit. It is most often used as a broad-level survey of community composition used to generate hypotheses based on differences between recovered gene-copy numbers between samples.

Metagenomics

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing aims to amplify all the accessible DNA of a mixed community. It uses random primers and therefore suffers much less from pcr bias (discussed below). Metagenomics provides a window into the taxonomy and functional potential of a sample. Recently, the recovery of representative genomes from metagenomes has become a very powerful approach in microbial ecology, drastically expanding the known Tree of Life by granting us genomic access to as-yet unculturable microbial populations (e.g. Hug et al. 2016; Parks et al. 2017).

Here we’ll discuss some of the things each is useful and not useful for, and then look at some general workflows for each.

Amplicon sequencing utility

- Useful for:

- one metric of community composition

- can say something about relative abundance of gene copies recovered

- can track changes in community structure (as interpreted by recovered gene copy numbers) in response to a treatment and/or across environmental gradients/time

- can help generate hypotheses and provide support for further investigation of things

- one metric of community composition

- Not useful for:

- abundance of organisms (or relative abundance of organisms)

- recovered gene copies ≠ counts of organisms

- gene-copy number varies per genome/organism (16S sequence can vary per genome)

- pcr bias (small scale) -> under/over representation based on primer-binding efficiency

- pcr bias (large scale) -> “universal” primers, only looking for what we know and they don’t even catch all of that

- cell-lysis efficiencies

- recovered gene copies ≠ counts of organisms

- function

- even if we can highly resolve the taxonomy of something from an amplicon sequence, it is still only one fragment of one gene

- hypothesis generation is okay, e.g. speculating about observed shifts in gene-copy numbers based on what’s known about nearest relatives in order to guide further work

- but, for example, writing a metagenomics paper based on 16S data would likely not be a good idea

- There is no strain-level resolving capability for a single gene, all that tells you is how similar those genes are.

- abundance of organisms (or relative abundance of organisms)

As noted above, amplicon data can still be very useful. Most often when people claim it isn’t, they are assessing it based on things it’s not supposed to do anyway, e.g., this type of question:

“Why are you doing 16S sequencing? That doesn’t tell you anything about function.”

To me is like this type of question:

“Why are you measuring nitrogen-fixation rates? That doesn’t tell you anything about the proteins that are doing it.”

We shouldn’t assess the utility of a tool based on something it’s not supposed to do anyway 🙂

Metagenomics utility

- Useful for:

- functional potential

- insights into the genomes of as-yet unculturable microbes

- much better for “relative” abundance due to no confounding copy-number problem and no drastic PCR bias (still not true abundance)

- still some caveats, like cell-lysis efficiencies

- Not useful for:

- abundance of organisms

- “activity”

- neither is transcriptomics or proteomics for that matter – each gives us insight into cellular regulation at different levels

General workflows

Amplicon overview

A Note on OTUs vs ASVs

All sequencing technologies make mistakes, and (to a lesser extent) polymerases make mistakes as well. Our initial methods of clustering similar sequences together based on percent similarity thresholds (generating Operational Taxonomic Units; OTUs) emerged as one way to mitigate these errors and to summarize data – along with a recognized sacrifice in resolution. What wasn’t so recognized or understood at first, is that when processing with traditional OTU-clustering methods, these mistakes (along with a hefty contribution from chimeric sequences) artificially increase the number of unique sequences we see in a sample (what we often call “richness”, though keep in mind we are counting sequences, not organisms) – often by a lot (e.g. Edgar and Flyvbjerg 2015, Callahan et al. 2016, Edgar 2017, Prodan et al. 2020).

Over the past decade, and particularly with greater frequency the past ~5 years, single-nucleotide resolution methods that directly try to better “denoise” the data (deal with errors) have been developed, e.g. Oligotyping (Eren et al. 2013), Minimum Entropy Decomposition (Eren et al. 2014), UNOISE (Edgar and Flyvbjerg 2015), DADA2 (Callahan et al. 2016), and deblur (Amir et al. 2017). These single-nucleotide resolution methods generate what we refer to as Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). The field as a whole is moving towards using solely ASVs, and – in addition to being specifically designed to better deal with errors and successfully drastically reducing the number of spurious recovered sequences – there are pretty good practical reasons for this also. This Callahan et al. 2017 paper nicely lays out the practical case for this, summarized in the following points:

- OTUs (operational taxonomic units)

- cluster sequences into groups based on percent similarity

- choose a representative sequence for that group

- closed reference

- + can compare across studies

- - reference biased and constrained

- de novo

- + can capture novel diversity

- - not comparable across studies

- - diversity of sample affects what OTUs are generated

- closed reference

- ASVs (amplicon sequence variants)

- attempt to identify the original biological sequences by taking into account error

- + enables single-nucleotide resolution

- + can compare across studies

- + can capture novel diversity

- attempt to identify the original biological sequences by taking into account error

If you happen to work with amplicon data, and are unsure of what’s going on with this whole hubbub between OTUs and ASVs, I highly recommend digging into the Callahan et al. 2017 paper sometime as a good place to start 🙂

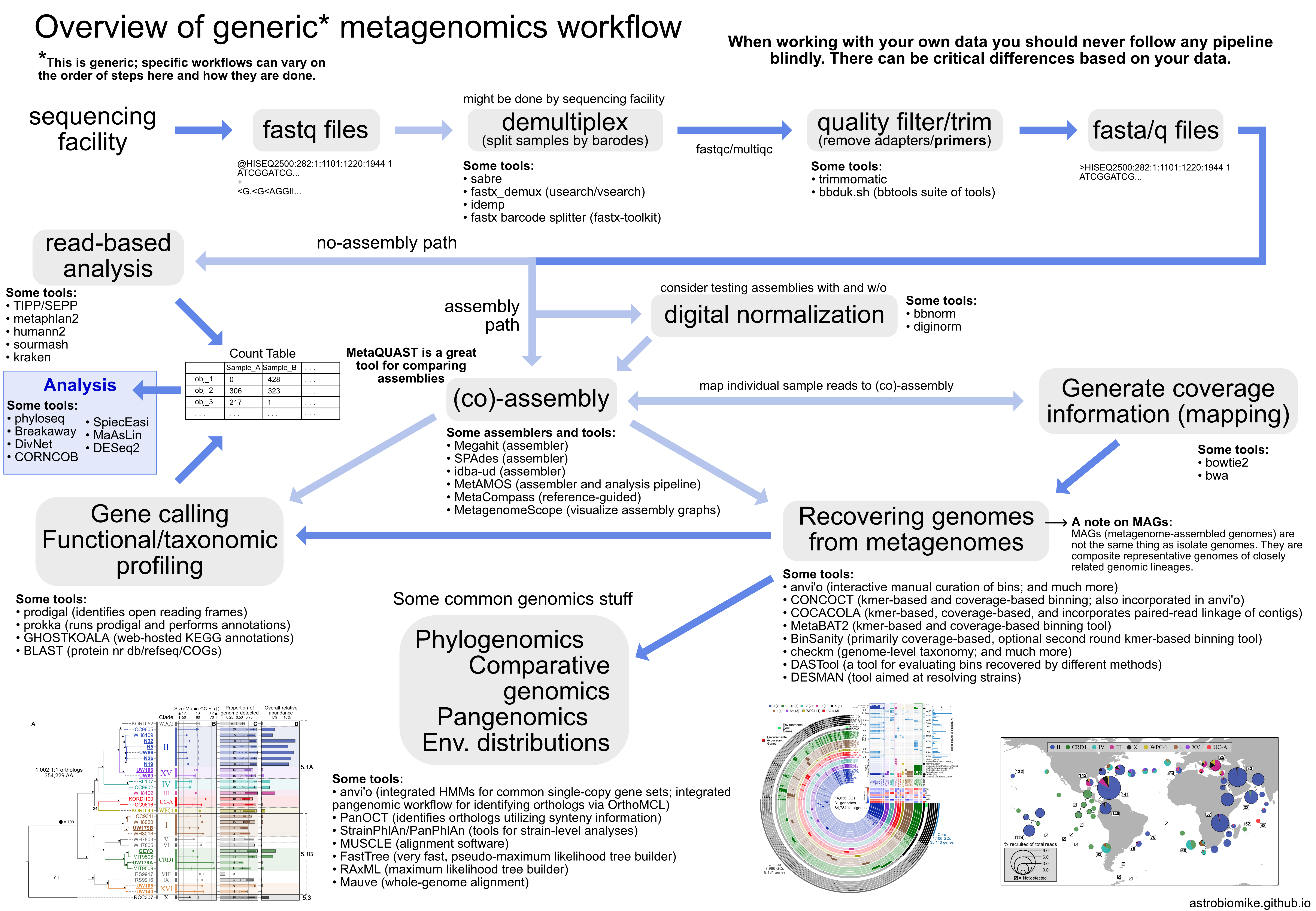

Metagenomics overview